About Basking Sharks

About Basking sharks

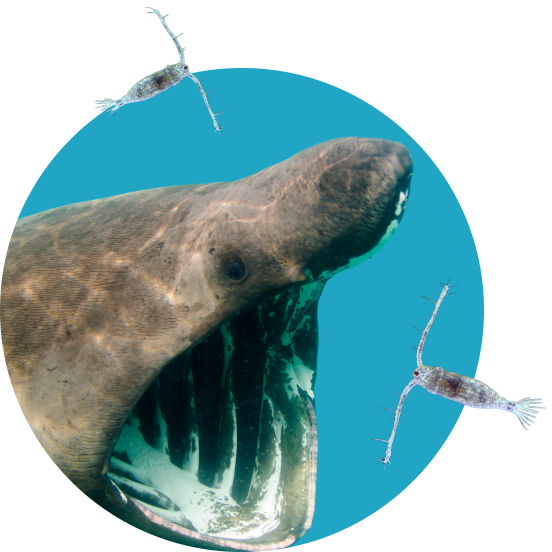

The basking shark, Cetorhinus maximus, is the biggest fish found in the British Isles, and the second largest shark species in the world – only the tropical whale shark is bigger. Similar to the whale shark they feed on a diet of only plankton, and are one of only three filter-feeding shark species.

The Sea of the Hebrides is one of the world’s largest basking shark hotspots, over the past ten years we have had lots of incredible opportunities to be part of basking shark research and have an ongoing data collection project.

These elusive sharks undertake huge migrations, spending a lot of time in deep waters offshore, and as such have not been as extensively studied as other shark species. Here is some of the information we currently know about basking sharks:

Taxonomy

Basking sharks have an unusual classification and are part of the order Lamniformes. This order is more commonly known as the mackerel sharks and ranges from great whites to makos, porbeagles and the megamouth shark. It seems strange to think that the famous seal-hunting great white is related to the plankton-eating basking shark, however, they share a similar fin and body type which is particularly noticeable when the basking shark closes its mouth revealing a much more streamlined silhouette.

Basking sharks are the last extant species in their family Cetorhinidae. Cetorhinus, the genus name of the basking shark originates from the Greek word ‘ketos’, meaning “marine monster” or “whale”, and rhinos, meaning “nose”. Read more about the basking sharks name in other languages here.

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Class: Chondrichthyes

- Subclass: Elasmobranchii

- Order: Lamniformes

- Family: Cetorhinidae

- Genus: Cetorhinus

- Species: Cetorhinus maximus

Distribution

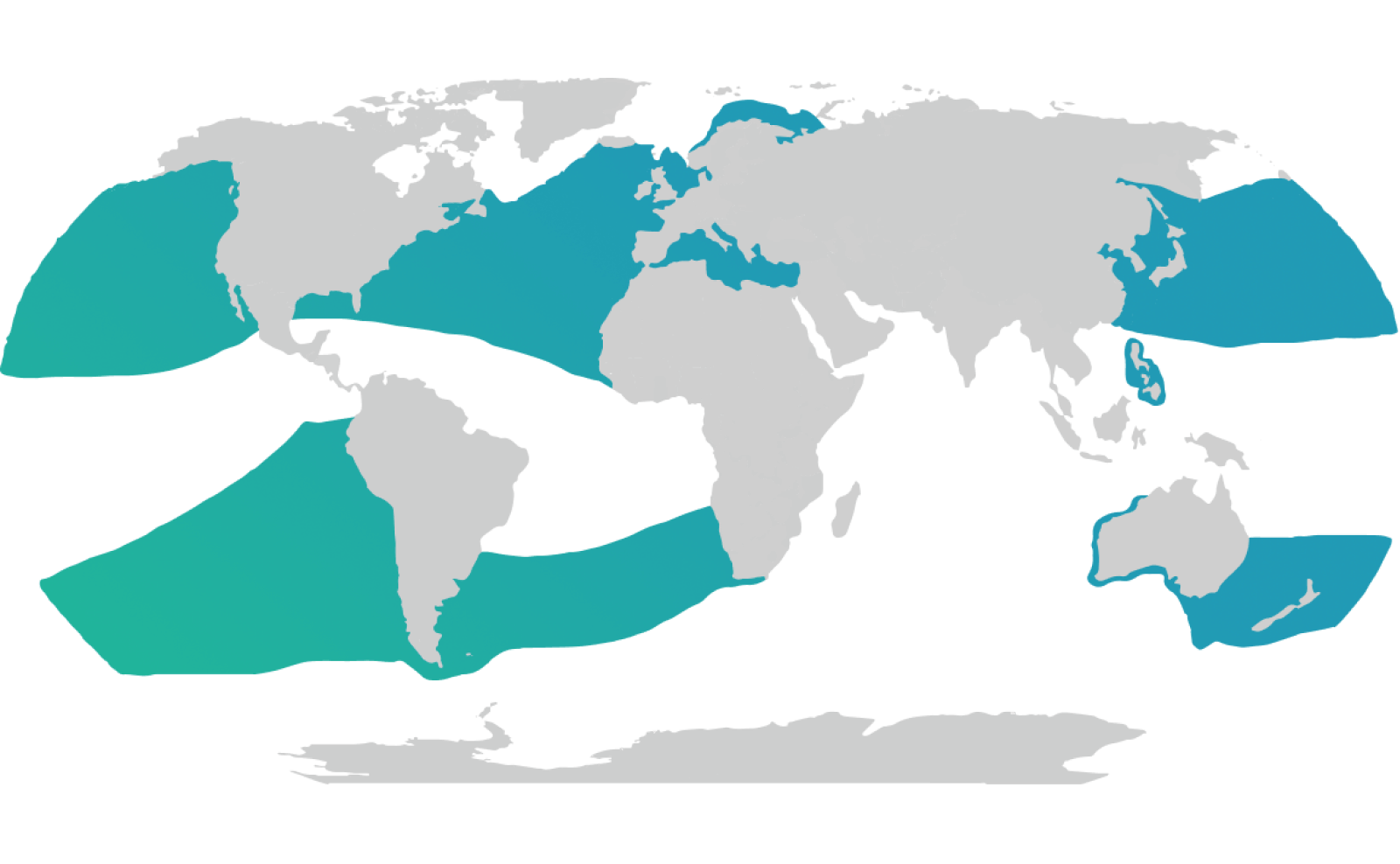

Basking sharks are found worldwide in both temperate and tropical waters, they are a coastal-pelagic species that undertake large migrations.

Migration Pattern

The North Atlantic basking shark population have a very interesting migration pattern which was relatively unknown until recent years. Satellite tagging programmes have increased our knowledge of site fidelity of the sharks, where it has been demonstrated that they are seasonally resident around the islands. It has also given us an insight into their autumn and spring migration to and from the Hebrides. Although they are seasonal visitors to our waters, there is evidence of some that stay over winter, with fishermen reporting them in mid-winter, divers witnessing them in deep water and even some washing up after bad weather or in poor condition.

The start of their main migration coincides with the first plankton bloom in the spring, with the number of sightings increasing in the summer months before they depart in the autumn. Sharks that have been tagged over this time have travelled incredible distances, making a transatlantic migration towards Newfoundland, with other sharks travelling towards the Bay of Biscay and the Azores. The reason for this stage of their migration is unknown and they are very conspicuous at this time. Studying them at this time is difficult due to their time spent offshore and in deep water.

Listen to our podcast about shark migration with Professor Mauvis Gore & Professor Rupert Ormond here.

Food Source

Scotland has some of the richest cold waters in the world. Every spring, oceanic conditions and weather cycles create optimal conditions for explosive blooms of plankton. With the increased availability of upwelled nutrients, higher sunlight and warmer temperatures, the plant-based phytoplankton generates large blooms. This sustains the zooplankton which is the food source of the basking shark.

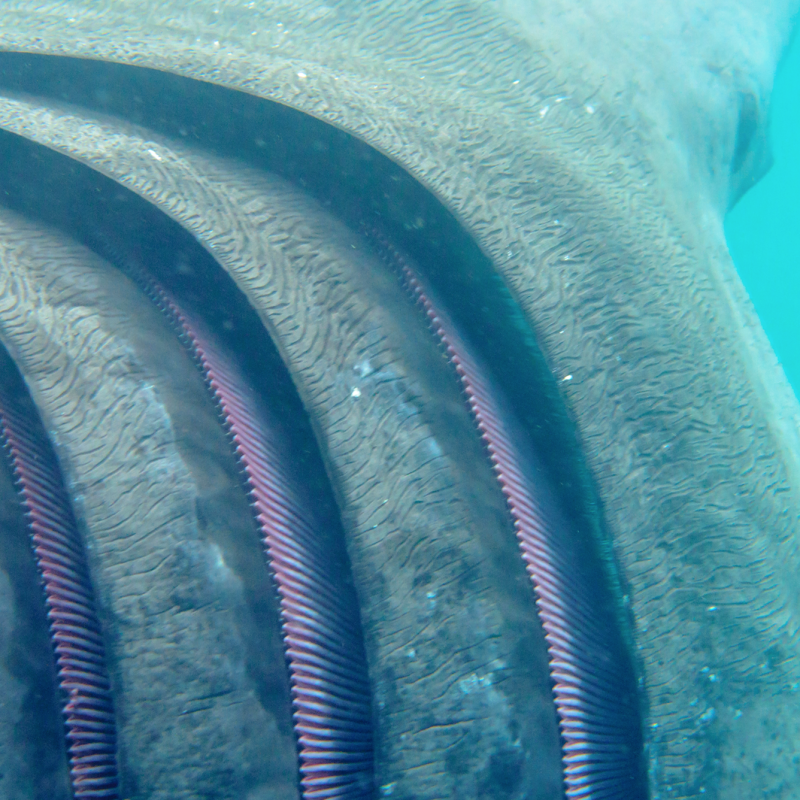

Zooplankton is a generic term for a multitude of species. There is a specific type of copepod – a type of crustacean, that the basking sharks prefer. The Calanus family, and in particular Calanus helgolandicus, are understood to be the meal of choice. During blooms of this specific species, the water is alive with a red-coloured bloom and we have abundant sharks who hone in on this food source. During our own studies we have found that whilst copepods can be abundant all over the coastline, the areas where the larger copepods are located have the most sharks. This does make sense as the sharks are getting more bang for their buck, gaining higher energy input for the same amount of energy used feeding.

Listen to our podcast about filter feeding basking sharks here.

Anatomy

Size

Gender

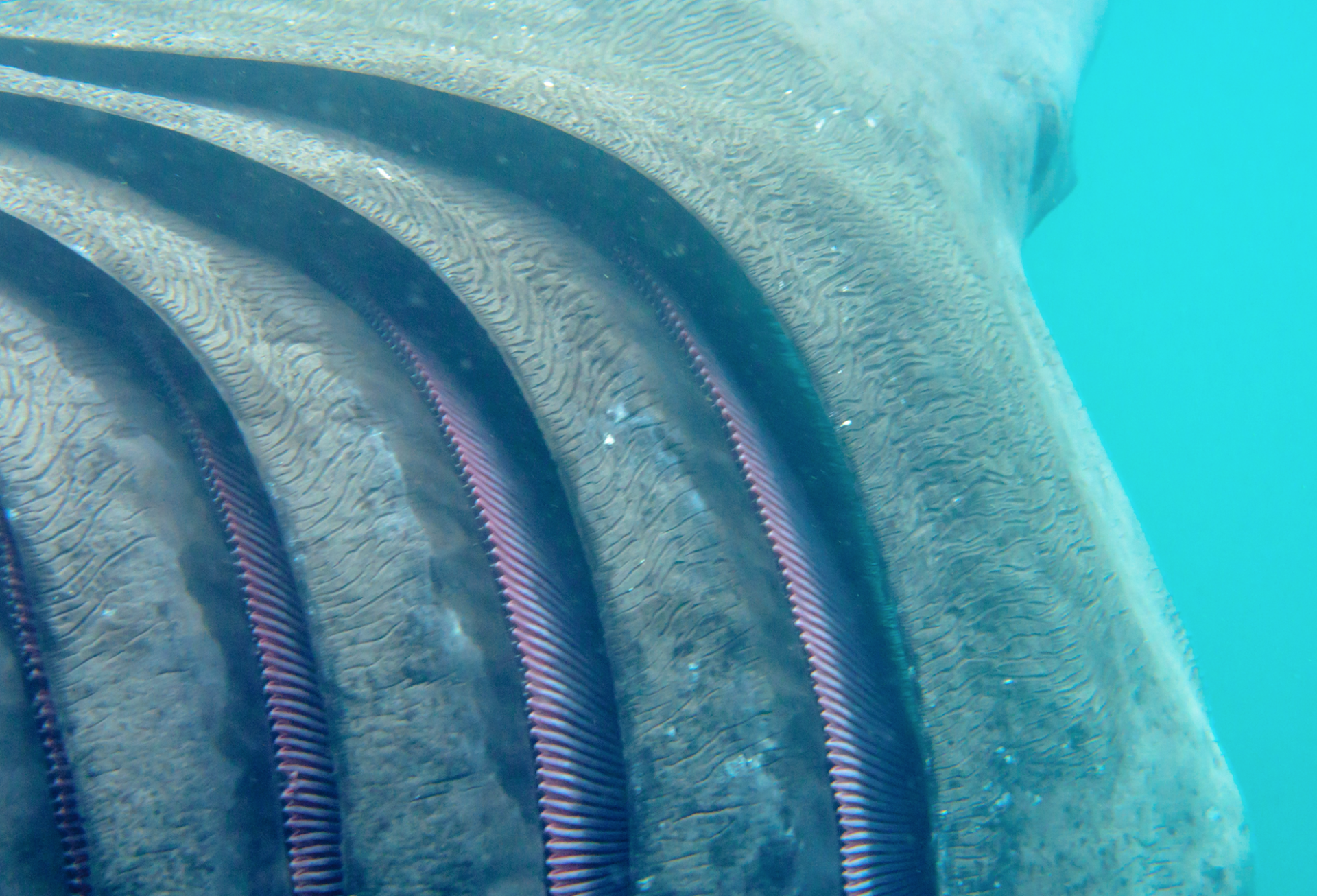

Mouth

Teeth

Skin

Liver

Brain and sensory function

Behaviour

Reproduction

Reproduction is poorly understood in this species, as this part of their life cycle has never been scientifically recorded. There is historic evidence of sharks rolling around at the surface together in what could be courtship, as seen by fishermen such as Howard McCrindle – a lucky man to have observed this! More recent evidence suggests that behaviours seen in the UK and Ireland are indicative of pre-courtship behaviour.

In the Hebrides, there are very few small sharks seen and it is thought that pupping occurs elsewhere. The sharks are ovoviviparous, meaning they first develop within an egg sac but are born live at approximately 1.5-2 metres long. The only record of this being seen was by a Norwegian fisherman, who upon catching a large female shark saw her give birth to one live and five stillborn pups. There seems to be more smaller shark sightings further south in the UK and even into the Mediterranean, however where basking sharks are giving birth is still unknown.

Breaching

Basking sharks can breach clean of the water, they are the largest shark in the world to do so. There seems to be a higher incidence of this in the Hebrides than in other areas and it is more frequent at times of large shark aggregations.

Although there is a theory that the breaching may be a way of ridding themselves of the parasitic lamprey, the energy required to breach would not seem to be worth the benefit of increased swimming efficiency. Any other display in nature usually relates to breeding and it is generally accepted that this behaviour is related to signalling in some way. We suggest either that the males are showing some type of dominance or attracting the female, or perhaps the females are signalling that they are ready for mating.

Breaching is also responsible for the only UK fatality recorded as a shark attack, known as the Carradale incident. Back in September 1937 a family was out fishing in a 15ft dinghy when a shark breached and capsized it. During this incident, three of the occupants died.

Conservation

Basking sharks are classed as endangered on the IUCN red list of threatened species after populations have severely declined. Although targeted fisheries for basking sharks have now closed, they are still impacted by bycatch, entanglement, ship strike, changing climates and marine debris. Read more on our blog here.

The sharks were historically hunted in Scotland, even as recently as 1994. They were targeted for their large livers which contain a vast amount of oil. Traditionally this oil was used in lamps, however, other industrial uses were found for the shark liver oil such as producing a constituent called squalene for cosmetics, perfumes and lubricants. Over the years it is estimated almost 100,000 basking sharks have been hunted, they are now protected in the UK, but with their migratory behaviour protection can not be enforced in other parts of their range. The sharks are still targeted in other countries for shark fin soup – it has been reported that one exceptionally large dorsal fin even reached $57,000 USD. A current threat to basking sharks is from marine debris and microplastics. They filter out their microscopic food source from the water and so much plastic has now entered the ocean and been broken down into small particles, the effect on the sharks’ gill rakers or even from ingesting these microplastics is unknown. A larger scale threat could be related to their food source.

Climate change has been noted to affect the range of their preferred prey species and has shifted their distribution northward, possibly replacing them with another warmer water species. These large-scale climate and oceanographic changes have unseen effects on the general public but can have dramatic repercussions on the marine environment. Change in the basking sharks’ food source could also affect their migration pattern and distribution.